The forces in our lives are constantly colliding—sometimes in ways that work out well and sometimes in ways that don’t. This interview series is an exploration of what it can look like to work with the collisions, rather than against them. By digging into how humans and nature interact– from our relationships with other humans, to those with our non-human neighbors, to our relationship with ourselves to our relationship with the landbase–we can uncover how to best step fully into our role in the story of the world.

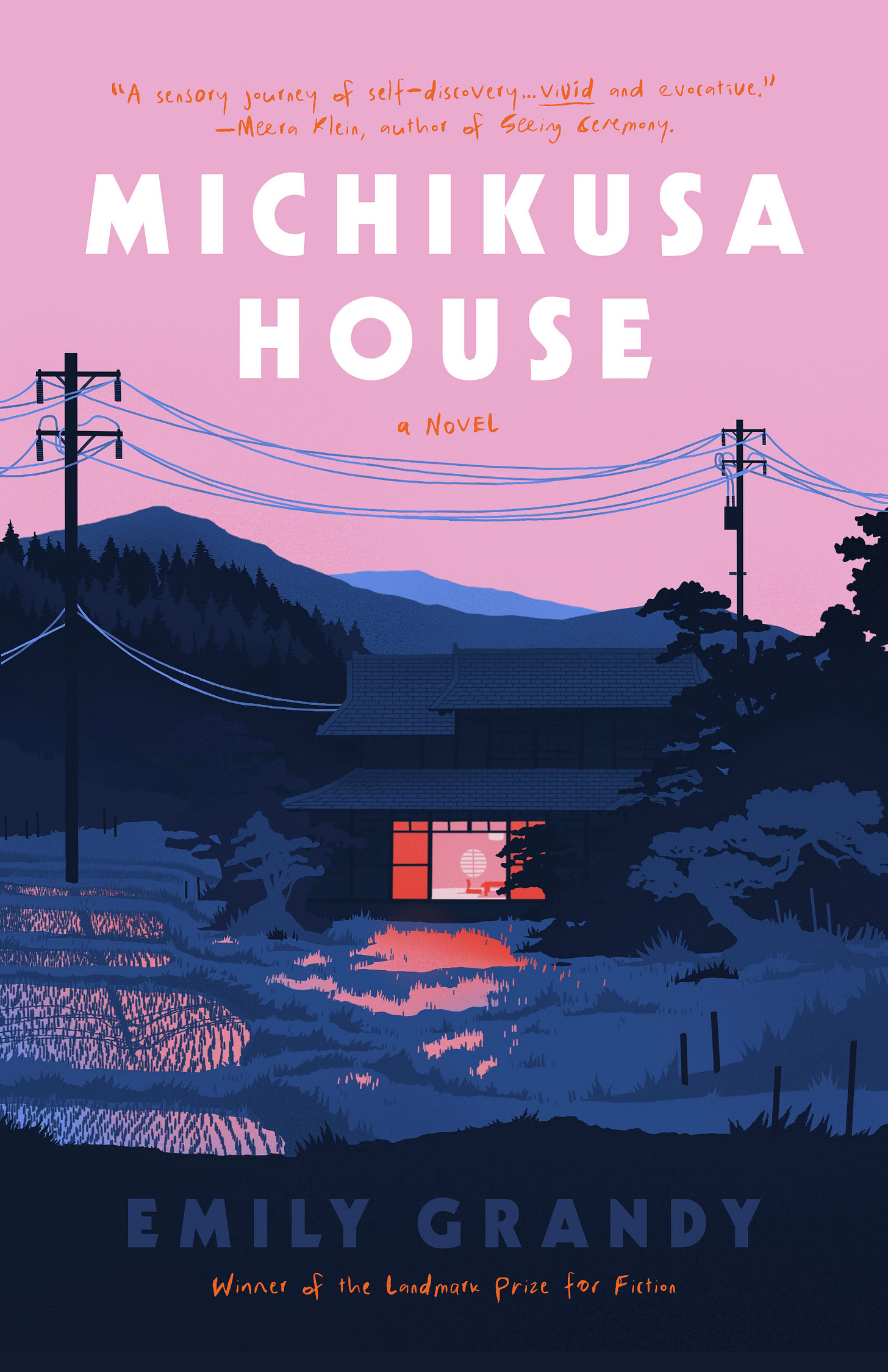

Today’s guest on the Ordinary Collisions Interview Series is writer Emily Grandy. From what I know about her work and writing, we both value nature connection, social justice/environmental advocacy, exploring diverse landscapes, and have deep roots in the Midwest. Before Emily became a biomedical editor, she did clinical research for a leading academic medical center. Last year, her debut novel, Michikusa House, was awarded the Landmark Prize by Homebound Publications. Her forthcoming novel, Cupido Cupido, was recently a finalist for the PEN/Bellwether Prize for socially engaged fiction. Her writing has appeared in both academic and literary journals and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She has lived in many places, but always gravitates back to the Midwest and its Great Lakes. She currently calls Milwaukee, Wisconsin home.

Heidi: Emily, Thanks for being here with us today. To start, I always ask the same question: What are two forces that are colliding in your life right now (or that have in the not too distant past)?

Emily: For roughly the last decade, the collision of science and spirit has been on my mind. For me, in my life and my career, these two forces have worked like two opposing magnets that refuse to meet or cooperate. In fact, virtually all my writing explores the reasons why science and spirit are divided. In following the theme of this interview series, today I want to talk about how and why I’ve endeavored to unite these two forces.

Before I go any further, I guess I should define “science” and “spirit”. In this context, I’m referring to the business of science, the methods by which it’s carried out, and how the results inform our choices. Specifically, I want to address medicine and biology, as my entire career has been dedicated to those fields (and therefore my critiques do not entirely apply to other disciplines, like physics). Later, as a patient, I also got to see how science translates to clinical practice…and how much can be lost in translation.

I’m using the word “spirit”, I admit, partly for the alliteration. But what I’m referring to is wholeness, connectedness, or oneness. The whole essence of a living being, not simply the biology. Even “nature” might be an appropriate stand-in here. As John Muir famously wrote, “When one tugs on a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.” Nature = Oneness.

Okay, moving on. So, let’s talk about why I see science and spirit as being divided.

A couple years ago, when I was still working in a lab, I began to feel disenchanted by the world of academia. Like any institution, science has its issues: its methods are imperfect, statistics can be manipulated, funding programs favor hot topics, and funding for medical research is typically only made available to projects with a tangible treatment or product that can eventually be billed to a patient’s insurance company. Aside from all that, the white male perspective and Western cultural bias predominate. My own experience within that institution revealed a further shortcoming: the reductive research program.

In my novel, Michikusa House, the characters grapple with this issue directly. One, an engineer, is said to “[see] the world as an engineering project, an object you can disassemble into its constituent parts which, once identified, can be fully understood. But reductionism only works for objects that can be cleanly separated; it’s an impractical method to apply to living, flowing, messy biology.”

The best example I can give to illustrate how much medical and biological science overlooks is this: think of the person (other than yourself) who you know best in the world. A spouse or your best friend.

Now imagine your loved one is enrolled in a scientific study in which the researchers’ aim is to understand everything about that individual. Every day, for a full year, let’s say, scientists from many disciplines will take notes and measurements: blood pressure, cholesterol, hand preference, psychological questionnaires, dream diaries, food intake and exercise, a biographical sketch, genetic profiling, you name it.

At the end, all the scientists pool their data and write a report describing all the metrics they collected and analyzed about your loved one (note that specialists across disciplines rarely collaborate in this way, preferring to work rather a lot in “isolation” within their respective niches). Their combined conclusion is that they now have a pretty good idea of who that person is. But would you say that even after a year of interaction that the scientists know your loved one better than you do? Probably not. Would you even be a little insulted if they claimed to know your loved one better than you do? Probably! Why? Because you are the one who has a relationship with that person. You’ve known them longer, you have a history together.

My point is this: scientific knowledge, via numbers, rates, and metrics, though undeniably useful and essential to human flourishing, forms an incomplete picture. It is just one way to know something. Forming a relationship is another way—a way to understand the Spirit, a way to know a person in their entirety. Developing relationships is what enriches our lives and gives deeper meaning to our daily interactions.

Indigenous or generational knowledge is also increasingly recognized for its essential wisdom. These ways of knowing can introduce us to the Spirit of every species, body of water, or stretch of land. After all, it’s not just people who are complex. Every living thing exists within an intricate ecosystem that is just as nuanced as the life and spirit of your loved one. This sort of knowing, built over long periods, is what facilitates understanding, compassion, and respect for other beings.

Heidi: I could down some many tangents about how metrics miss so many things…… Such an important thing to remember, and dominant culture doesn’t often support looking for nuance and prioritizing relationships. How are you navigating the conditions this collision is creating? How does the dissonance created impact your choices?

Emily: In my own writing, I want to share science-based knowledge through storytelling, but also instill a deeper level of respect for other ways of knowing, ways that connect us to the spirit—to the true nature—of other living beings.

Heidi: You’re offering your readers such a gift with that approach.

What has this collision taught you about yourself? The world?

Emily: I mentioned earlier that I eventually I ended up as a patient for a chronic medical condition at the same institution where I worked, arguably one of the best medical research centers in the country. As in the lab, the physicians and psychologists I met seemed not only to have their own beliefs and agendas, but also viewed me not as a person but as a collection of symptoms to be diagnosed and treated. On the flip side, I also had doctors completely dismiss my symptoms as “all in my head,” an unfortunately common habit known as medical gaslighting. I can’t even recall how many specialists I saw, but across the board they ignored my “spirit” in favor of their “science”. After many years slogging along in this way, and after spending a small fortune, I finally found relief and validation outside Western medicine.

Ancient healing practices like Ayurveda, for instance, take a more holistic approach toward health and wellbeing. In Eastern and Indigenous medicine, the aim is not necessarily to treat the symptoms, but to discover why the symptoms arose in the first place. This involves examining diet and sleep habits, exercise and activity, stress levels, our relationships, even the seasons and the weather can influence a person’s flourishing. Because these elements shift from day to day, the aim is not to find “a cure” but to achieve balance across all aspects of one’s life. Only after extending care to each element of my entire self—to every part of my spirit—versus treating only the symptoms, did I finally begin to find wellness. It is a much longer process, goodness knows, but the rewards, in my experience, are far superior and significantly longer lasting.

My symptoms never fully vanished, but I learned an important lesson: the resolution of pain is not the end goal of holistic living. Pain is actually an essential component of health. It teaches you listen to your body and respect its needs. Eventually you can learn to notice the minute shifts in your body's energy, your emotions, and then respond accordingly to rebalance the equilibrium before you even approach the pain stage. Practices like yoga, meditation, and massage which work to recalibrate the mind, body, and breath are therefore considered to be not the occasional hobby, accessible only to those who can afford spa treatments and island retreats, but essential components to wellbeing.

Heidi: Oh my gosh yes. I can relate to this so much from my own experience with a lingering illness. Listening to our bodies, and trusting what they share, is so important.

Can you tell us a bit about a collision you explore in your book that’s due out soon?

My debut novel, Michikusa House, tackles this issue—the collision between science and spirit—head on. In the book, the main character is a young woman recovering from an eating disorder. Although she’s healed in body, she hasn’t yet found a reason to want to get better. Thanks to a family connection, she ends up spending a year on a small family farm in rural Japan, digging—quite literally—into the rich food culture of that country, learning to grow vegetables and cook in concert with the seasons. In fact, she’s learning to cook for the first time in her life. In this way, she begins to reconnect with the living world, while simultaneously shedding long-held beliefs about shame, identity, and renewal. After returning to her hometown in Ohio, she fails to find that same sense of wholeness and connection in her undergraduate nutrition science program. Ultimately, she abandons the goal of obtaining a degree in favor of reconnecting with earth, taking a job as a groundskeeper at the historic cemetery behind her apartment.

Although it is entirely a work of fiction, Michikusa House draws on my own healing experience. It takes a critical view of contemporary nutrition science and American food culture while exploring the transformative power that comes from connection with other living things, humans and non-humans alike.

Heidi: I did my master’s thesis on eating disorders and I come from a family of organic vegetable farmers, so I’m really looking forward to reading!

Have a collision you’d like to explore in this space? Send me an email at heidi@heidibarr.com.

Thank you for sharing this insightful interview, it opens ones mind to whole new ways of thinking about life, and how we relate to the world and each other.

Love this! I ordered the book last week... can't wait to read.